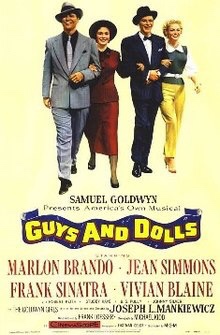

The great songs in Guys and Dolls are back-ended, as it were. Luck Be A Lady and Sit Down You’re Rocking The Boat play as the film moves to its climax in the Broadway Mission Hall. Of course, the plot, adapted from the New York stories of Damon Runyon, is preposterous.

High rolling gambler Sky Masterson wins the heart of Mission leader Sarah Brown after falling in love with her while winning a bet that he can persuade her to have dinner with him in Havana. That was in the days when Cuba was more or less an American colony: he later pays up on the bet, rather than collecting his winnings, for plot reasons. Somewhere along the line he gets a whole bunch of notorious mobsters to turn up for a midnight prayer meeting after winning their compliance in a hand of craps, for all honest gamblers must make good their markers. Luck be my lady…

Like I say, the plot is preposterous, but of course it is. For one of the points about the film musical is that it creates a place where the normal rules are suspended, where the improbable, or even the impossible, can happen.

The disciplinarian naval captain will fall in love with the ditsy governess; the seven brothers will meet and marry the seven sisters; the showgirl will become a star; the show will go on. Even in West Side Story, which (spoiler alert) doesn’t end well, part of its power is that it doesn’t end well.

Despite everything

Indeed, one of the reasons that West Side Story has the power it has is because, in a musical, one can believe that the Italian-American boy can marry the Puerto Rican girl despite everything. Perfect bitch that it doesn’t work out that way.

But, of course, the magic has to be concealed and revealed: Finian’s Rainbow, which is literally about magic, is a complete clunker, despite the talents of Fred Astaire, Petula Clark, and Tommy Steele. And Absolute Beginners, a serviceable if erratic film, fails as a musical because it misses this basic point; it lacks this transformational arc.

This perhaps helps to explain why the heyday of the musical, broadly from the mid-1930s to the early 1960s, happened when it did. By the 1960s, as the consumer revolution took hold and our homes filled up with stuff, economics was a perfectly credible route for the improbable. We could afford cars and washing machines and so on just by applying ourselves at work.

This might suggest that in the age of the 0.1% the musical is due a comeback. In La La Land, which gets some of the way there, they both achieve their goals despite the obstacles. But Danny Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire–real life magic–and Kinky Boots both seem more authentically improbable stories.