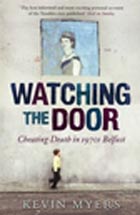

I was in Belfast and Derry last year on holiday, and while I was there read Kevin Myers’ fairly recent memoir of reporting the Troubles in the north of Ireland 35 years ago, first for RTE and later as a freelance. You realise, some way in, that you are watching a man coming to terms with post-traumatic stress. He never says it, of course, and my saying it here is not intended to diminish a well-written and compelling book. But about half way through Watching the Door, he admits us to a dream he had, every night for several years, even after he has left the city.

The men appeared out of nowhere. They were masked and armed and said not a word. Both raised their guns, but only one fired at me, hitting me neatly in the neck, and down I went, on my back. I knew I was doomed, that the wound was fatal. My spine was severed, and my trachea torn open. The two men walked over to finish me off … As I began to speak, the air merely bubbled through the bullet hole in my trachea, splattering boiling hot blood over the ice-cold rain on my face. Then they fired.

The catalogue of killings is relentless – he acknowledges his debt here to David McKittrick – the violence remorseless, his own part in it all captured on the page. In the introduction, he describes his role as being that of ‘a maggot’; at the end, working now as a freelance, the final straw is the La Mon tragedy in which 12 people were burnt alive:

Each penny earned in this way now depended on someone’s death. No killing, no money. The relationship was immutable and unavoidable. A fireman watching television in the base earns the same as a fireman fighting an inferno. Not me. I needed bodies. After my initial report about Le Mon I told NBC to look elsewhere.

The psychology of the violence is well captured, as is his increasing distaste for it. A story about a powder-blue Mercedes, owned by one of the two drivers who ferry him around for the Irish broadcaster RTE when he first joins the station’s Belfast bureau seems to stand for it all. The driver is shot by a soldier while changing a battery within sight of an army barracks. The Catholic car dealer who buys it from his widow, and his business partner, are both killed by the UDF when they drive it on business to the Protestant Shankill Road area. The hooded body of one is left on the back seat. The car, now unsaleable in Belfast, is sold cheaply through a Dublin newspaper: the new owner died in the vehicle on the way back south after losing control on a bend.

Belfast was [in 1972] now like that Mercedes: cursed from on high, and violent and terrible death awaited the unwary at every turn and every hour. … Every morning brought a harvest of bodies of the stupid, the unlucky and the gullible who had died terribly. Protestants and Catholics were equally likely to fall victim to this lethal mood.

The life of a journalist in such circumstances inevitably becomes complicit, to the point of becoming a target. One of the UDA hard men tries to kill him (he’s saved by a tip-off from a companion); he flees from a planned beating by the IRA; a pistol is cocked to his head by a member of the Paras; he stumbles out of the debris of a pub bombing only because he happens to be in the urinals when it explodes.

It’s an honest story, well told. I think he may be too hard on himself, looking back at 60 on his 20-something self, for I am not sure that others would have fared better. Buried in the story are several occasions when he did the right thing, either as a journalist or as a person, sometimes at some risk to himself. And he’s sharp on the British government and the British Army’s place in the conflict, and their blindness to the role played in the conflict by the UDA and UVF loyalists.

In a memorable passage, he observes that Belfast in the 1970s had, as a city, become clinically insane. He starts by believing that he understands its madness, but realises that the longer he stays the less true this is. He’s walked into a world, and a time, which is impossible for an outsider fully to grasp; he’s tolerated for a while by those who live there while he suits their purposes, but he’ll never learn their codes and private meanings.